Reimagining digital transformations

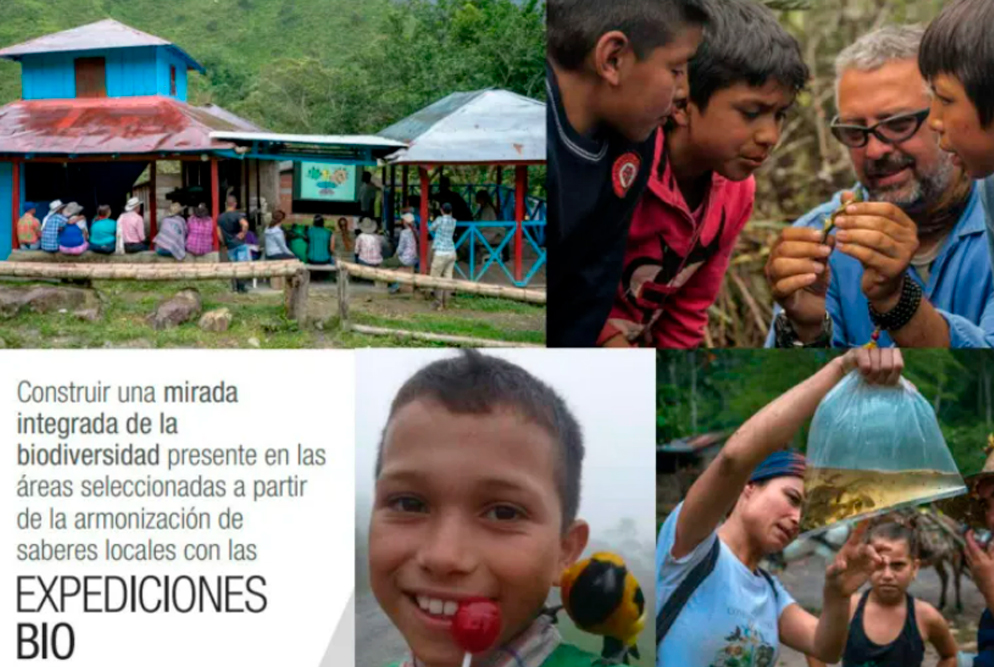

Participatory design (PD) is a powerful methodology that can be applied to re-imagining digitalization process, bringing ethical considerations to the foreground, and fostering the inclusion of multiple stakeholders and diverse people in all the phases of the process. Since its origins in the 1970s and the context of the workplace, PD aimed to democratize power and decision making, empowering workers, communities and people as designers. That is, empowering all people, independently of their background and expertise, as creative agents capable of ideating, planning, and prototyping services, objects, spaces, and tools. Sometimes called co-design, other times co-creation, PD is a radical approach to working with communities that radically embraces dialogue, cooperation, and horizontal relationships. In the midst of the multiple pressures for implementing ICT and data-driven systems across all dimensions of human life and society, PD offers a range of tools, protocols and techniques, that can facilitate more horizontal and participatory processes where diverse voices and perspectives can meet and work together in the implementation of new technological infrastructures, services and products.

Last year I facilitated two virtual workshops about PD for two groups of international graduate students from around the world and diverse disciplinary background. The workshops were included in two research clinics co-hosted by the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society (AI Policy with the City of Helsinki) and the Digital Asia Hub (Cities, Digitalization, and Ethics) and supported by the Ethics of Digitalization initiative. This initiative consists of a series of educational programs (mainly research sprints and clinics) developed by the Global Network of Internet and Society Research Centers (NoC) to advance dialogue and action at the intersection of science, politics, digital economy, and civil society, and to help translate AI ethics and governance principles into practice. Embracing the values of openness, networking, interactivity, collaboration, dialogue, and participation, these transdisciplinary educational programs have proven to be innovative and transformative, assembling a diverse group of students from different backgrounds and connecting them with academics, entrepreneurs, policy makers, designers, and experts from multiple sectors.

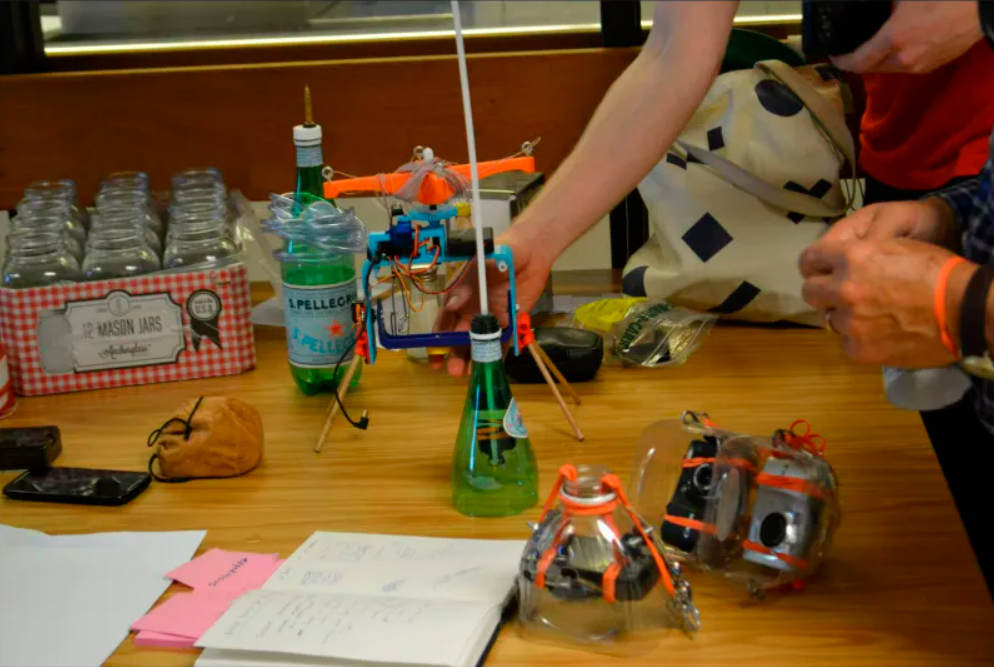

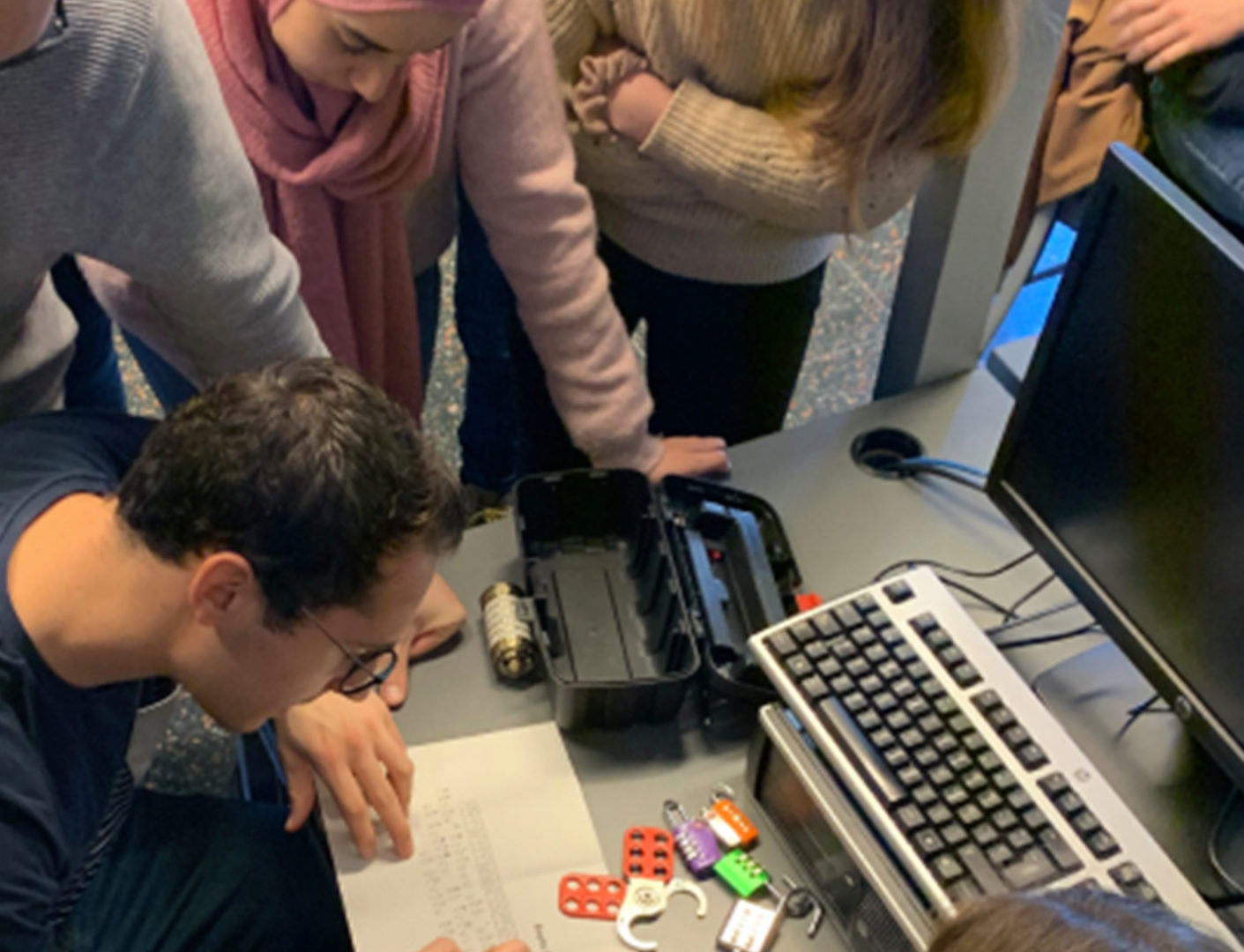

The PD workshops mixed theory and practice providing the participants with basic methodological foundations, examples of PD in action, and a sample of tools and techniques they could apply right away through practical exercises. The workshops combined short presentations, discussions, and collaborative group exercises (e.g. ecosystem mapping, persona maps, speculative fiction). Aligned with the goals of experiential learning, the workshops allowed students to think and apply the PD methodology for solving real problems of governance and ethics that cities around the world are confronting nowadays or in the near future. For instance, in the AI Policy Research Clinic students tackled the problem of re-imagining the governance of an AI system aimed to support learning, student wellbeing, and retention in Helsinki’s vocational schools, and re-considered strategies and tools to make it more inclusive, transparent, trustable, and participatory.

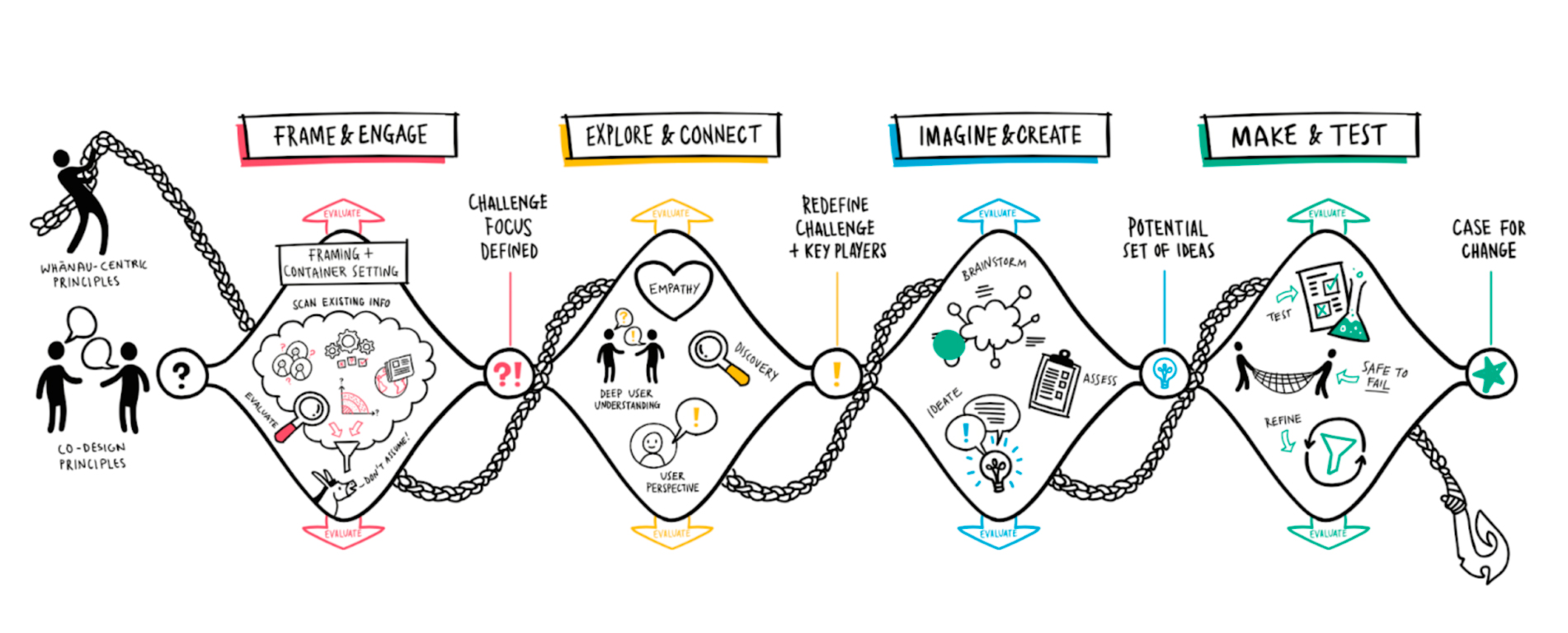

As cities around the world increasingly become driven by digitalization and data, it is crucial to develop strategies to bring ethics into practice. That is, to go beyond the mere acknowledgement of ethical principles, and start applying them in the actual design and implementation of data-driven systems. PD methodology provides protocols, tools and techniques that can help to achieve that. Its major advantage compared to other methodologies, is that given its political and ethical foundations, PD fosters a radical inclusive approach in where all the phases of the design process (empathize/research/connect, define, ideate, prototype, play test) are not only doing for people, but doing with the people.

More exactly, PD is an approach in which all stakeholders and potential users of the service, product or object need to be included in the process. Of course, there are limitations and problems with such inclusive and democratic approach, mainly the one related to the orchestration of diverse crowds, and the need of time and space to plan, meet, and discuss. It is not the most efficient methodology in terms of speed, and goes in the opposite direction of many of the methodologies that are used by entrepreneurs and policy makers that want to do fast implementations, disrupt, and break things fast.

In preparation for the workshops, I shared the following short list of references:

- Bratteteig, T. and G. Verne. 2018. Does AI make PD obsolete? Exploring Challenges from Artificial Intelligence to Participatory Design. In Proceedings of PDC 2018, Belgium, August 2018, 4 pages.

- Mattern, Shannon. (2020). “Post-It Note City,” Places Journal, February 2020. Accessed 07 Jul 2021. https://doi.org/10.22269/200211

- Sanders, E. B-N., Brandt, E., & Binder, T. (2010). A Framework for Organizing the Tools and Techniques of Participatory Design. In K. Bødker, T. Bratteteig, & D. Loi (Eds.), Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference 2010: PDC 2010 Participation :: the Challenge (pp. 195-198). Association forComputing Machinery (ACM). ACM International Conference Proceedings Series

- Sunlight Foundation. Guide to co-design: Learn how to create a participatory design process.

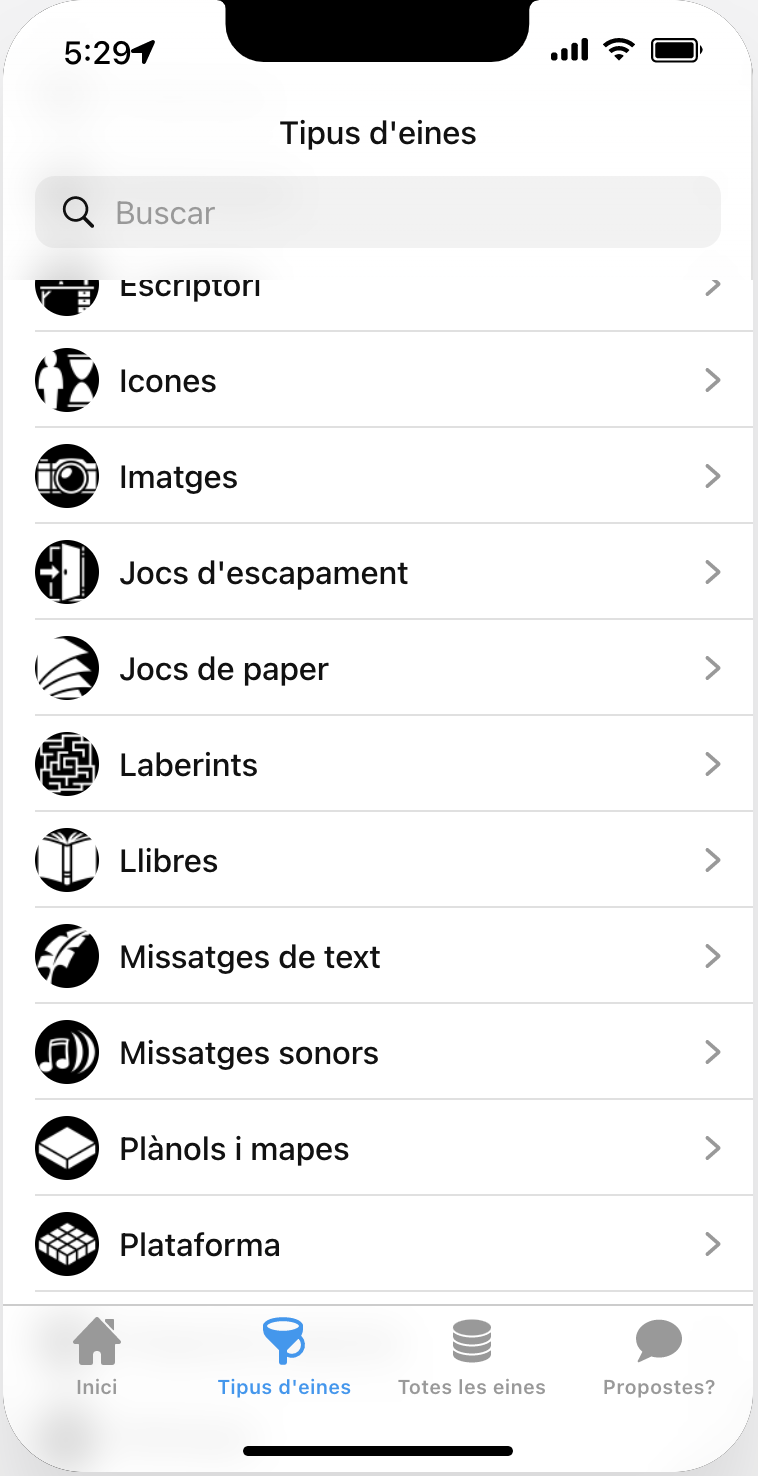

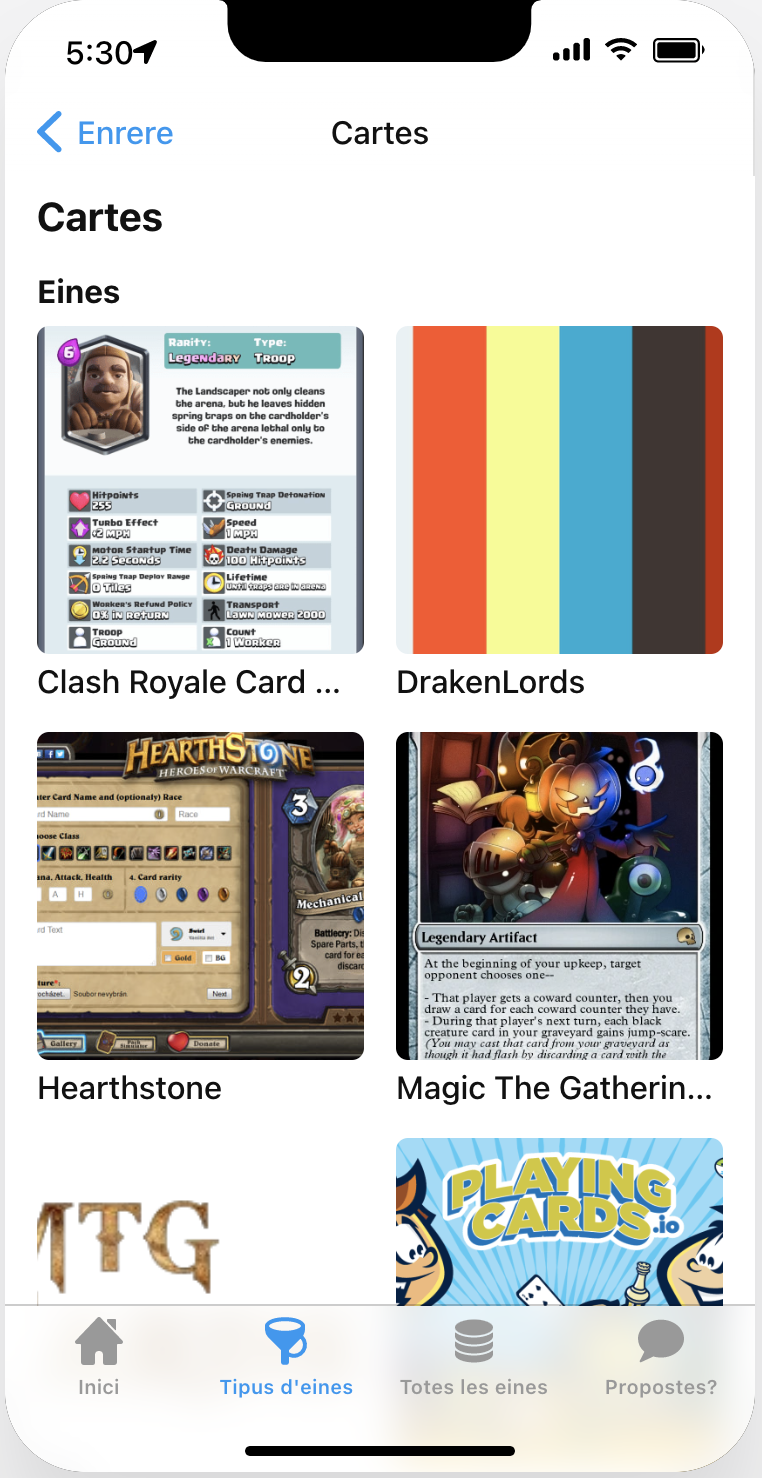

A sample of PD tools and techniques

I also curated and shared a sample of participatory design tools and techniques available on the web. The range of tools can be overwhelming, but fortunately there are several projects and sites that have organized them and presented them as learning guides and tutorials.

From the Auckland Co-Lab https://www.aucklandco-lab.nz/resources

From the Community-led design wiki